The first person to write an algorithm was a woman in the 19th century. But in the 21st century, algorithms may end up reinforcing gender stereotypes.

Even though the first person to write an algorithm was a woman in the 19th century, artificial intelligence may now be discriminating against women.

Two centuries on from the first example, algorithms "have the ability to push us back decades" in gender parity, explains Susan Leavy, a researcher at University College Dublin who is part of a project to prevent Artificial Intelligence algorithms from learning gender bias.

"They can exacerbate toxic masculinity and the attitudes we have been fighting for decades in society," she adds.

The burden of history

Artificial Intelligence (AI) learns from data that is made available, and most of it is biased, says Leavy.

The problem is that machines learn from data from the last 10 to 20 years which can unwittingly reproduce prejudices from the past. Moreover, without incorporating more recent social advances regarding gender and attitudes, the language and phraseology used in the data can perpetuate out-of-date stereotypes.

For example, most AI hasn't heard about the global feminist movement #MeToo or the Chilean anthem "a rapist in your path."

"We continue repeating the mistakes of the past," says the researcher.

And this bias in programming has an impact on the daily life of all women: from job searches to security checkpoints at airports.

Pioneers in the world of programming

Ada Lovelace (1815-1852) became the first programmer in history, a century before computers were invented.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the British mathematician wrote what is considered to be the first algorithm for a computer machine devised by her colleague, scientist Charles Babbage.

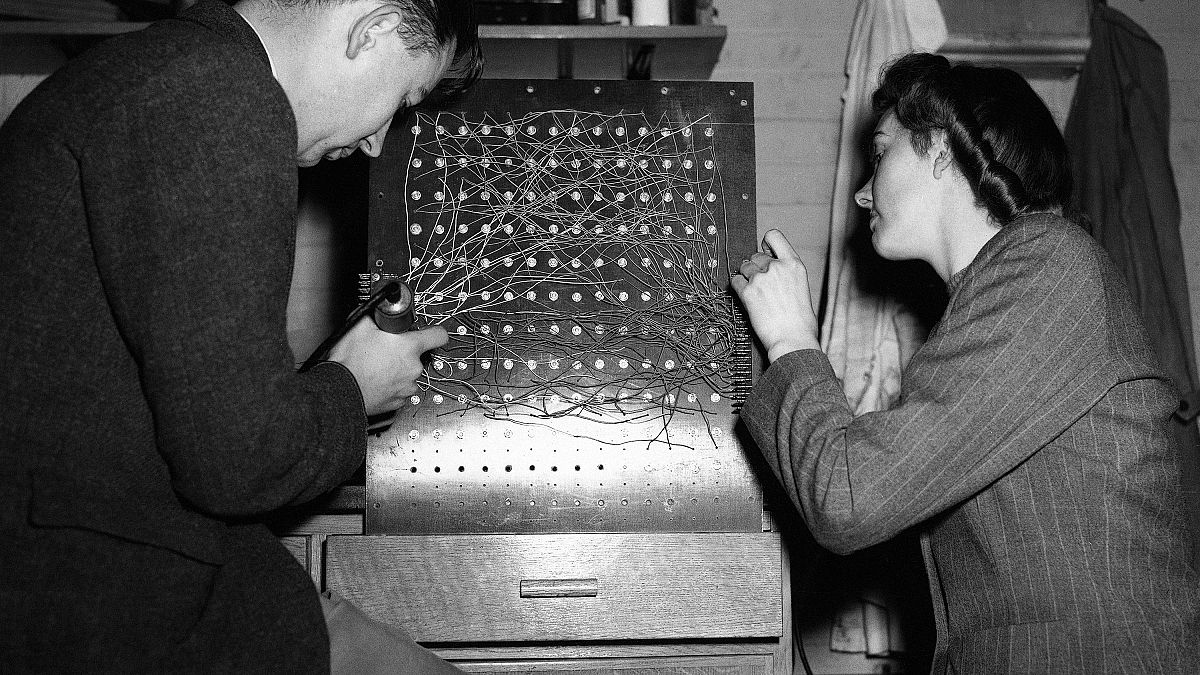

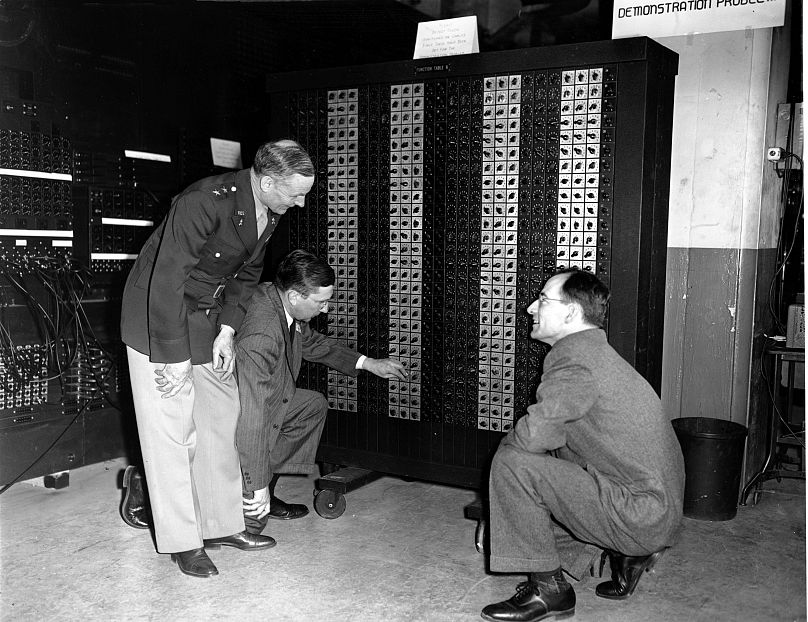

In fact, many of the pioneers in the world of programming were women. They were considered better at minute tasks - such as the ENIAC programming (an acronym for Electronic Numeric Integrator and Computer).

As part of a secret US Army project in World War II, six women programmed the first electronic computer. However, their names were omitted when it was presented to the public in 1946.

Male overrepresentation in sciences and technology

The programming sector became more male-dominated in the 1980s. Even today, 59 per cent of Europe's scientists and engineers are men, according to the latest Eurostat data.

This inequality was inadvertently and unconsciously integrated into the writing of the algorithms.

"There is a big problem of gender disparity, especially in the machine learning process," underlines Leavy. "This means that there is a lack of critical perspective."

But is it possible for male programmers to pinpoint exactly the bias they are bringing into their work?

"I don't think most engineers want to develop algorithms that discriminate based on gender or race," Leavy says.

But it is not just a matter of intentions. According to Leavy, it is best to have diverse programming teams to prevent machines from absorbing prejudice in the first place. "We know that teams that are not diverse do not produce good results."

Leavy also recommends that tech-companies have their products tested by female members of their teams.

How do algorithms discriminate against women?

"Al and other algorithmic technologies now shape our lives in ways both significant and mundane," explains Joy Lisi Rankin, a leading researcher on gender, race and power in artificial intelligence at the AI Now Institute in New York.

"We rarely understand this because the technology is invisible to us, and the way it works is not at all transparent," she continues.

These algorithm systems determine, for example, "who has access to important resources and benefits," she adds.

One of the best-known cases of discrimination based on the use of AI was Amazon's attempt at automating their recruitment system.

In 2018, it came to light that the American multinational had discarded its AI tool, with which it had been selecting candidates applying for jobs for four years, because it was sexist.

Amazon's computer models had been trained by to vet applicants by looking at patterns in CVs submitted over the ten previous years. However, considering it is a male-dominated industry, most of these resumes were men's, creating a machine-learned-bias that favoured male applicants.

"Resume selection is a very problematic area," observes Leavy. "Even if you tell AI algorithms not to look at gender, they will find other ways to find out."

Amazon's algorithm penalised resumes that included words related to the female gender, even in the hobbies of the candidates, such as "captain of the women's rugby team."

It is not only a matter of gender, but this type of algorithm also punishes any kind of diversity, by privileging a series of patterns that end up favouring the most privileged and represented part of society: white men.

Facial recognition systems are another problematic algorithm, explains the researcher. "If you are a woman with dark skin, it will work worse."

The consequence may be slight, for example, if your phone costs more to unlock with your face, but it can also mean having difficulties when passing a security check.

"If you are a white man who goes to an airport, you get a quick pass, if you are a woman with dark skin you have a much better chance of waiting in a longer line."

Another area in which sexist algorithms are having a crucial impact on women's lives is search engines and social networks.

"They categorise and treat users differently taking into account a series of stereotypes," says Leavy. The "most dangerous" is when they use these ratings to send personalised advertising, particularly to young people who are more easily influenced, notes Leavy.

Rankin gives us an example: "Facebook posted ads for better-paid jobs to white men, while women and people of colour were shown ads for less well-paid jobs. Google searches for 'black girls' or 'Latinas' produced sexist and pornographic results."

What if they help us fight sexism instead of perpetuating it?

The new European Union regulations for the development of AI indicate "growing awareness," says Leavy.

It is an issue that the European Commission under Ursula von der Leyen is promoting and prioritisin. "It may take us 10 years," she adds.

For this to happen, she says that multidisciplinary teams must be involved, with the perspectives of both men and women represented on the teams.

The algorithms could also help us fight discrimination, including sexism in recruitment processes. A machine could be more impartial than a human when selecting candidates - if it has learned to be inclusive.

"I have to see more evidence of this to believe it," Leavy notes, adding that she does believe algorithms have the potential to be unbiased.