The viral start-of-year challenge invites women to embrace their natural body hair for a month. But why is body hair - especially on women - still so controversial?

Scroll through the @januhairy Instagram account and you’ll find stories from women around the world who’ve chosen to cast their razors aside for the first month of the year.

The tone is overwhelmingly triumphant. A woman with a buzzcut wearing a pink halter top with hearts painted on her eyes gleefully raises her arms, revealing two tufts of armpit hair. She exclaims: “I’m a woman and I have body hair! One sentence does not exclude the other, because body hair is natural.”

Another with a curly blond bob and bright blue eyes dances giddily as she strokes her leg hair and shows off her underarm fluff. The video starts with big on-screen text reading: “Hey guess what? Women grow hair too!”

But dig a bit deeper and you’ll find that Januhairy isn’t just another lighthearted start-of-year self-improvement challenge. Some of the testimonies on the page reveal deep insecurities and even shame that women have felt about their body hair.

A 13 year old from Australia writes: “It’s still hard to embrace my hair out in public, mainly cause I don’t want attention and eyes on me, with disgusted looks.”

Her fear is logical when you take into account some of the downright hateful comments on Januhairy’s posts:

“If you think this is attractive you’re sick in the head”

“If you don’t wanna shave ok but that’s not hygienic! Just saying”

“No guy is gonna settle for a femal (sic) with chest hair”

The visceral hatred towards women’s body hair may be surprising for some – it is 2024 after all, shouldn’t we be over this by now?

But moral philosopher Heather Widdows, author of "Perfect Me: Beauty As an Ethical Ideal" and professor at University of Warwick, says the way society views body hair (on both men and women) has only become more hostile over the last decades.

“Something like Januhairy, it's a political statement, it's not a personal choice,” Widdows told Euronews Culture. “It's not like giving up alcohol in Dry January. It's not something that people have got neutral views on. It's something that to do it, you have to be making some kind of big political statement rather than a fashion choice.”

What is Januhairy?

Januhairy began in 2018, an initiative by Laura Jackson, at the time a drama student at the University of Exeter in the UK. Jackson told British media that the idea came after she had to forgo shaving for a performance.

"Though I felt liberated and more confident in myself, some people around me didn't understand or agree with why I didn't shave," she told the BBC at the time.

The social media campaign spread quickly and soon reached women from around the world. On top of raising awareness of the stigma still surrounding women’s body hair, the first edition also raised money for a charity that educated about body image.

Over six years, the @januhairy Instagram account has amassed over 40,000 followers.

It’s a rare instance of body positivity on an app that’s more often a breeding ground for unattainable beauty standards.

“If we want to use some broad strokes, social media is usually not very helpful for women's body image,” says Professor Elizabeth Daniels, head of UWE Bristol’s Centre for Appearance Research. “The effect, though, tends to be somewhat small.”

For Daniels, the more powerful influences – especially on younger women – are peer groups and targeted beauty marketing.

“There's so much out there that's pushing in the other direction and that's telling women, you need to shave to be considered beautiful,” Daniels told Euronews Culture. “So to be able to shut all that out and think about, what do I consider to be beautiful, what do I want to willingly participate in in terms of beauty practices, is a really tall order for individual girls or women.”

When did body hair become so controversial?

Western society’s perception of body hair as something that’s dirty or disgusting is relatively new.

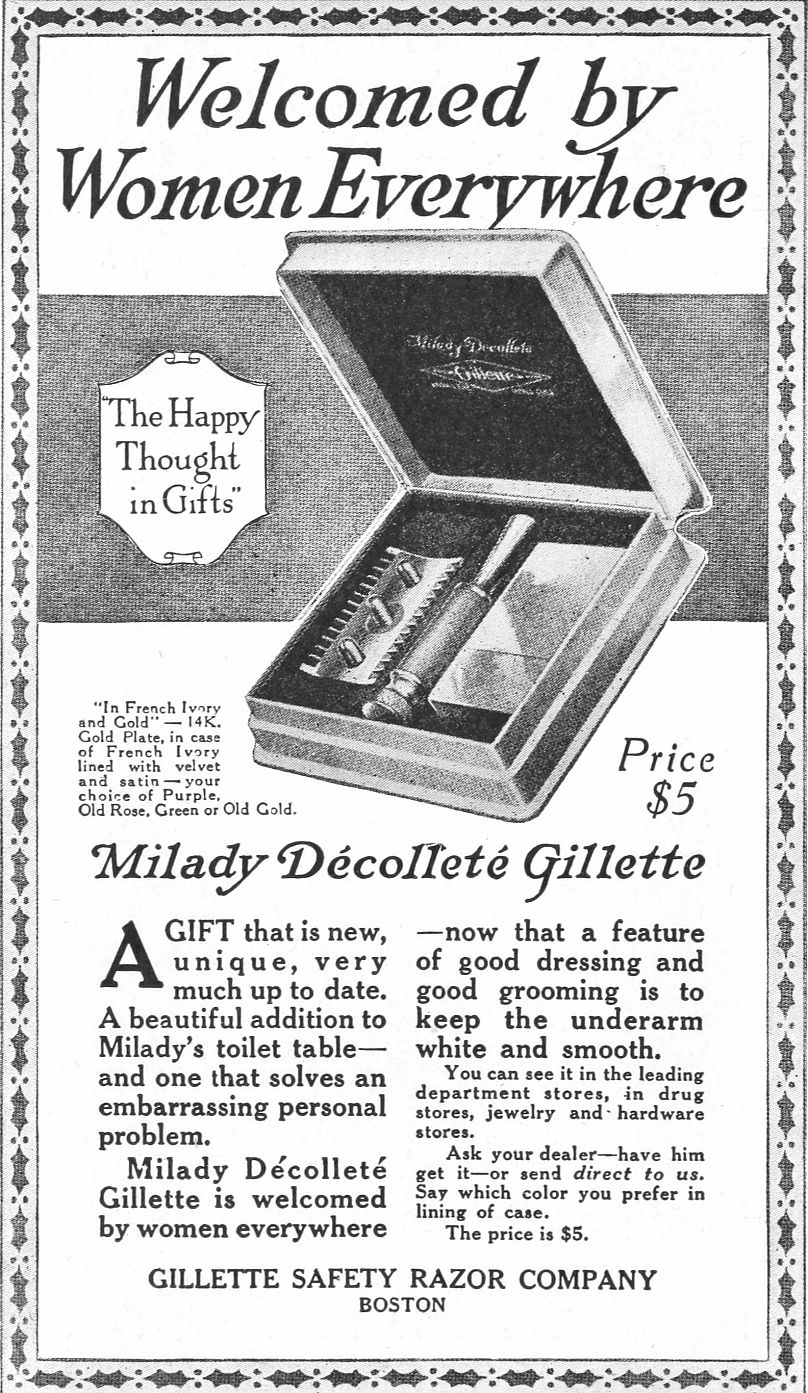

It wasn’t until the early 20th century that US razor company Gillette – still the largest shaving company in the world today – began targeting women in their advertising campaigns as a way to solve the “embarrassing personal problem” of body hair.

An ad dating from 1915-1917 reads: “Gillette is welcomed by women everywhere – now that a feature of good dressing and good grooming is to keep the underarm white and smooth.”

Before then, body hair removal in the West was reserved for the wealthier classes and done primarily for religious or practical reasons, to purify the body or prevent lice.

By the 1950s, as hemlines rose and capitalism tightened its grip on society, more women were shaving than ever and the image of hairless legs and underarms became a symbol of feminine beauty.

Body hair removal has only grown in popularity since – aside from a short reprieve during the bush-loving 1970s.

Today the global hair removal industry is booming. In 2022, it was valued at around $1.14 billion (€1.04 billion) and is expected to reach $1.89 billion (€1.74 billion) by 2032.

Research firm Mintel’s 2023 UK Shaving and Hair Removal Market report found that 55% of UK consumers – both men and women – had removed underarm hair in the last 12 months.

At this stage, body hair removal is more than a passing trend – and while there is an increasingly visible contingent of female celebrities and influencers embracing natural underarm hair, they’re swimming against a powerful social current.

“The normalising of body hair removal has gradually increased,” says Widdows, whose book ‘Perfect Me’ addresses the changing beauty ideal and its effects on our perception of self.

“Not to remove body hair is seen as not taking care of yourself, in the same way as not cleaning your teeth,” she adds. “It's no longer really regarded by many people as a beauty practice, but increasingly as a health and hygiene practice.”

Non-visual challenges for a visually-obsessed culture

According to Daniels, social media movements like Januhairy likely won’t have sweeping effects on how body hair is viewed on a global level. But they can change individual attitudes, and more importantly, they can spark conversation.

“It gives us the opportunity to talk about all of the expectations that women have to navigate constantly around appearance, whether it's shaving or wearing makeup,” she said. “There’s a lot of cognitive effort that women have to put into their appearance because of social pressure and expectations, so I think it’s a good opportunity to talk about those issues.”

For Widdows, however, the premise of movements like Januhairy and other body-positive trends on social media is inherently flawed.

“The intention is wholly good, but the effect might be counterproductive,” she explains. “Like very many body positive campaigns, it draws attention to the body rather than away from the body.”

On top of that, Widdows says, Januhairy only challenges one of the four features of the “global beauty ideal” that she lays out in her book.

She argues that for the first time in history, there’s a global consensus that in order to be considered beautiful, a person must possess thinness, firmness, smoothness and youth.

While posting pictures of hairy underarms and legs on social media rejects the “smoothness” aspect of the global ideal, most of the women participating in Januhairy are still thin, firm and young, Widdows observes.

“When that happens, then really what your images are saying is that this kind of body is the acceptable kind of body,” she says. “It doesn't challenge the ideal. It in fact reinforces it by challenging only one feature of it.”

So what’s a girl to do when she wants to fight the patriarchy without reinforcing beauty norms?

Both Daniels and Widdows suggest non-visual challenges that can help put body image and beauty standards into perspective.

Widdows started the #everydaylookism campaign to harness the power of personal stories around body shaming.

“We share our stories of body shaming and negative comments about how we look to show that it’s not okay and get that collective action going, to stop saying things about other people’s bodies,” she says.

Daniels challenged her students not to look in the mirror for three days, to see how it made them feel navigating the world without a visual representation of themselves.

“It was really interesting to hear their worries and their concerns that they wouldn’t be appropriate, like that they wouldn’t be okay to go out in the world – both men and women,” she said.

“I think it taps into this pressure that we feel that our appearance is being monitored.”