Cases of the highly infectious disease cholera rose in the last week in the poorest French region located off the coast of Africa.

Cholera cases rose significantly in the last week in the French overseas territory of Mayotte, doubling over the weekend and increasing since after health authorities issued an alert.

The regional authorities told Euronews Health that there are now 37 confirmed cholera cases as of May 1, up from 26 on Sunday.

Mayotte is an island and the poorest French department located north of Madagascar near the Comoro Islands, where a cholera epidemic is ongoing.

The infectious diarrhoeal disease caused by a bacterium can, in severe cases, be fatal within hours if left untreated, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

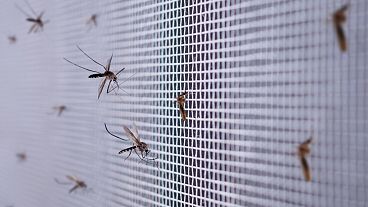

Cholera is spread by contaminated food or water and often affects communities without access to safe drinking water. Most cases are asymptomatic, but people infected with the bacterium can still infect others as it is present in their faeces.

Unknown ‘real state of cholera in Mayotte’

Antufaty Hafidhou, president of the organisation France Assos Santé in Mayotte, which represents patients in the health system, told Euronews Health that the number of actual cholera cases is likely much higher than what is reported.

“Basically, if we can count the cases as the [health authorities] do today, it’s made up of only those who present themselves at the hospital, however, there are still some who don't show up at all [in hospital],” said Hafidhou.

“Since we can't calculate the real state of cholera in Mayotte, it’s a worry for us because [cholera] transmits very easily and quickly without us being able to really manage it,” she added.

One of her concerns is the number of cholera cases in migrants arriving on the island, which has large migration flows from the neighbouring Comoros.

The French minister for overseas territories, Marie Guévenoux, told broadcaster France 2 two weeks ago that the government had mobilised 1,700 police and military as part of a new 11-week operation to take down slums and address irregular immigration.

The government’s operation last year, however, faced criticism from NGOs with the crackdown being denounced as “neo-colonial” and with calls for more funding to address poverty on the island.

The standard of living in Mayotte is seven times lower than the national level in France with 77 per cent of inhabitants living below the poverty line, according to government figures from 2017.

Hafidhou says there are migrants “who sleep on the road or the side of the road and who [defecate] around where they are. That too is another difficulty for us”.

“We are afraid that this will [aggravate] these kinds of difficulties which already exist in Mayotte,” she said.

Are vaccination and health controls enough?

The first case of cholera was detected in Mayotte on March 18, with Guévenoux saying that the response strategy has been to enable “its rapid detection and treatment”.

“All measures are being taken to stop the spread,” she wrote in a post on social media, as health officials in the region said contact tracing was underway.

Mayotte’s Regional Health Agency (ARS) said on April 28 that there were testing and vaccination operations ongoing over the past several days. A second “cholera unit” was also opened at a medical centre.

The ARS had previously said in February, amid the outbreak in the Comoros, that there were more health controls at the border and reinforced “field interventions” to stem any epidemic risk.

Hafidhou told Euronews Health that vaccination will help to stop the situation but “not 100 per cent”.

“People are scared,” she said, adding that the cases are around Koungou, the island’s already "overpopulated" second-largest city.

In the neighbouring Comoros, meanwhile, there were 3,703 cases of cholera as of April 30 and 78 deaths. The country’s health ministry warned people not to drink untreated water from lakes, rivers or ponds as it could be behind the spread of the epidemic.

UNICEF underlined in a report in March the difficulty of accessing drinking water in Mayotte, which is paralysed by shortages, adding that a cholera epidemic on the island would be “a disaster”.

Hafidhou says in Mayotte, people have access to water for three days before access is cut for 24 hours.

“We are very used to not having drinking water access in Mayotte, but we live like this because we don’t have a choice,” she said.

When asked whether the French government has done enough to address the situation, Hafidhou said “generally, in Mayotte, the situation degenerates before there’s an effort to address things”.